Introducing The Qi Fieldnotes Series

From Pilgrimage to Practice: Note-taking and Storytelling Across Spiritual and Scholarly Journeys.

"Look within. Within is the fountain of good, and it will ever bubble up, if you will ever dig."

— Marcus Aurelius

Attn Qualitative Inquisitor,

As I mentioned in my last edition, the next several editions of The Qualitative Inquisition will feature a few selected stories from my recent journey to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). But before I begin sharing those reflections, I wanted to pause to say a few things about the role of note-taking in qualitative research, especially when conducting qualitative fieldwork.

I did intend to write an article about taking field notes. But with my first international trip in years, specifically in the KSA, I saw an opportunity for some gentle practice.

I have been very passionate and super anxious to explore fieldwork further for over six years now. I was happy to have a small opportunity to practice some reflexivity, ethnography, and participant observation skills in my travels to Saudi Arabia, even during the spiritual journey of the Pilgrimage.

Once you develop that skill as a social scientist or a qualitative researcher, it is difficult to escape the cultural anthropologist within you, no matter the purpose of your travels.

It’s also symbolic. You can never fully prepare for going into the field, and sometimes, like this KSA trip, you are gifted an incredibly transformational experience in a new world, unexpectedly. A world that you want to view and respect with fresh eyes, and an open mind and soul.

As I said, my direct interaction with “the field” has been minimal for a few years now. Opportunities to travel don’t come easily for most of us. I would like to allow this series of newsletters to be field notes—alive with memory, place, and presence, sharing the stories, and even potentially triggering a deep dive into previous stories from past field expeditions.

So this series will begin by unpacking my most recent “field expereince,” where I will explore various layers of my Pilgrimage journey: the travel, the food, the people, the language, the spiritual process, powerful moments in both Madinah and Makkah, the mosque architecture and expansion efforts, the internal and external challenges, and the deeply visceral experience of it all—one story at a time.

I have around seven to eight entries lined up so far (that may change as I review my notes and photos), so I hope since I had limited posts the past year, that you would be open to a couple more emails than usual from me the next few months, so I can share these while the reflections are still raw and warm.

On Note Taking: A Field Companion

In qualitative research, note-taking is a critical skill and an entire practice (Busetto et al., 2020; Poth & Searle, 2021). It is the most fundamental way to be present and to witness all that is happening around us.

Field notes are a critical part of our data. They are stories, and stories are data too (Muswazi & Nhamo, 2013). You feel something from them more than you would from any other data point. Fieldnotes allow us to capture our thoughts at the very moment of an encounter. And those thoughts can also be from reflections post-encounter, post-interview (Muswazi & Nhamo, 2013; Maharaj, 2016; Pope et al., 2000).

The subtle pauses, the diplomacy of laughter, the unspoken dynamics, the smell surrounding you, the gut reactions, the contradictions.

This is life in the field site, the research setting.

Field notes preserve that moment, and they also become a portal to remember, a way back into the moment, and to ask more interesting questions.

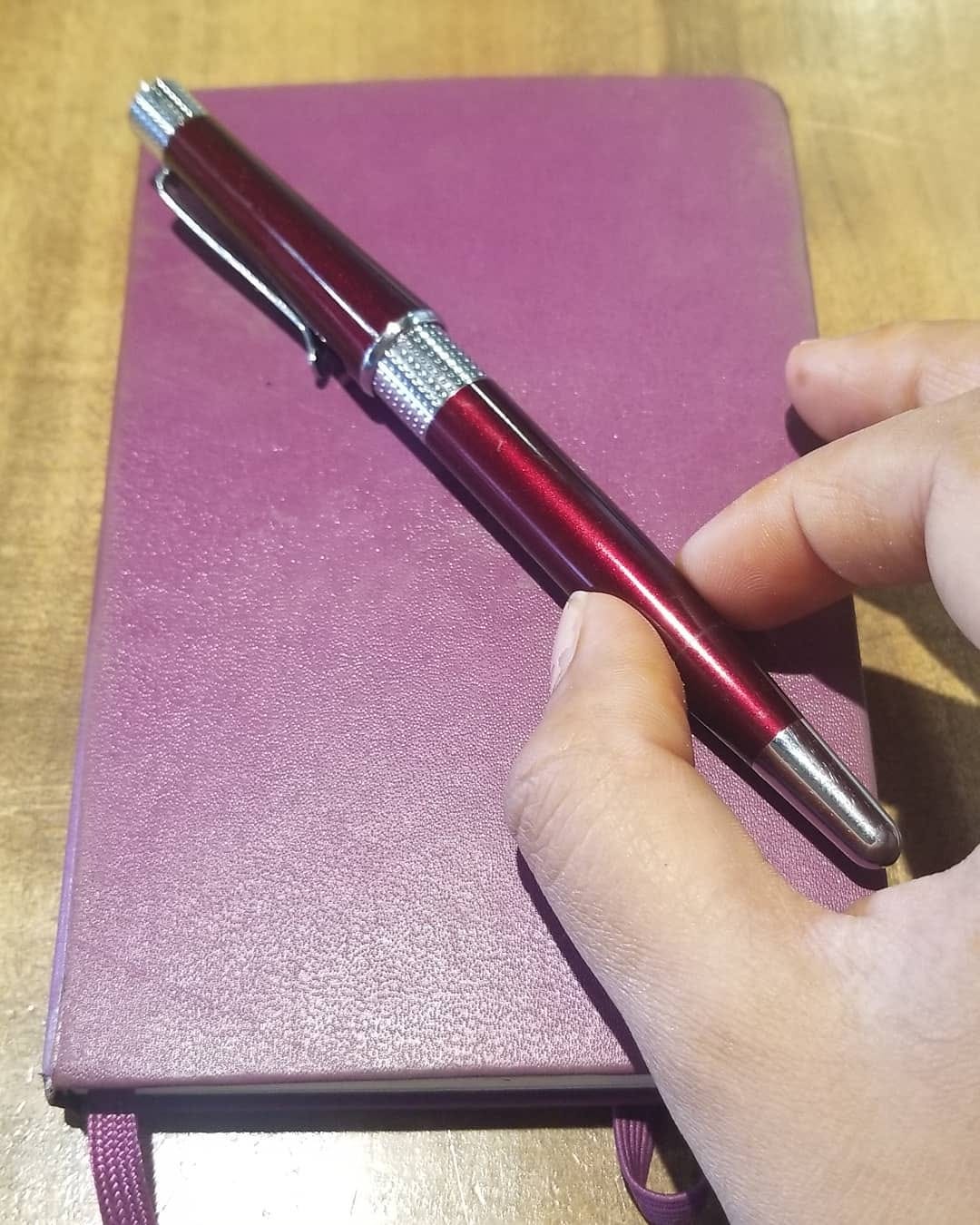

No Need for the Fancy Tools

A pen. Some paper.

And your memory.

That’s more than enough.

I found it quite romantic that the same pen I used for fieldwork across major cities in Pakistan came with me to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It became my field companion.

There’s something special about that. Especially the continuity in the craft of writing, fieldwork, and fieldnotes in general.

We write not just to record observations, but to remember, to reflect, to reclaim.

I would like to revisit key elements from both my doctoral and master's fieldwork in Pakistan for the following editions, making this transition from the themes of "Identity" to "Fieldwork" feel especially timely.

Here is a blast from the past, in NaniSer, Tharparkar, Sindh. I remember sharing this on social media at the time, claim that “this is all I need in life: A baby goat in my arms, a pen, and a notebook.” See, no need for any fancy tools!

I am glad my memory still serves me, but this photo was about a very special, unforgettable moment, discovering a land I never thought I’d visit in my parents’ home country, in the same province we would always travel to as kids.

I know I will need to rely on my memory, my fieldnotes, and interviews when I can come back to this work or complete my book projects.

Trust Your Memory

Your brain is powerful. As Jim Kwik reminds us, don’t ever say you have a bad memory. Say you have an untrained one (Kwik, 2020).

Because what we often need is not more tools, but more trust and confidence in ourselves. I know I can attest to this.

Photos help. Artifacts help. But memory, reflection, and the discipline of noticing while in the field are where some of the most exciting insights emerge.

Photos and artifacts may even help to bring you back to those moments (Harper, 2002; Pink, 2013; Rose, 2016). I took nearly 35,000 photos in my fieldwork in Pakistan (2017-2019). I still believe it could serve as a great visual ethnography project at some point, should I not make it back to Pakistan soon.

Visual materials such as photographs and artifacts can serve as powerful anchors for memory and reflection, helping researchers return to the emotional and sensory context of a moment (Harper, 2002; Pink, 2013; Rose, 2016).

Our memories are more powerful than we give them credit for. It’s called neuroplasticity, and with the right kind of training, we can significantly improve how we store and recall information (Kwik, 2020).

Photos, voice memos, artifacts, even smells, all help us access memory. But nothing replaces the practice of showing up, observing fully, and writing it down in real time (or soon after). Those lasting impressions are often the raw material for insight.

Qi Reflection Prompts

What did you feel in the moment you were observing, and how might that feeling shape what you chose to write down or emphasize?

What moments or details did you ignore, rush past, or choose not to record? Why do you think that is?

In what ways do you show up in your notes? What do your notes reveal about your perspective, presence, or position?

What parts of the research setting stayed with you long after you left, and what might that lingering reveal about the emotional layers of your work?

What sensory experiences (smells, textures, sounds, temperatures) shaped your perception of the field, and how do you express those in your writing?

Note-taking Is Not a Linear Process

You can take notes before the fieldwork even begins—through anticipation, mapping, and journaling. It can happen in scribbled fragments, sketches, emotions, drawings, and questions.

I found myself putting red hearts next to observations that moved me. It certainly happens after — in reflection, in dialogue, in moments that revisit you unannounced.

Note-taking also isn’t just documentation. It’s a critical reflection (Maharaj, 2016; Roller, 2017; ). Muswazi and Nhamo (2013) highlight that effective note-taking involves discerning and recording critical information rather than transcribing conversations verbatim. This approach ensures that notes are tailored to the research objectives (Pope et al., 2000; Poth & Searle, 2021).

Effective note-taking involves asking ourselves: What did I notice? Why did I notice it? How do I feel about what I’m seeing, and why does that matter? This last part may not be important to some, but it is just as critical in our evaluations.

Note-taking becomes a tool of reflexivity. As I noted in one of my previous editions on Reflexivity, it helps us examine our positionality, recognize our biases, and understand the relational dynamics at play.

Handwriting notes, especially, can help with retention, encouraging deeper engagement, active listening, and immediate reflections that could lead to more nuanced data collection and analysis (Roller, 2017).

It’s not about capturing everything. It’s about learning to see — strategically, compassionately, and honestly.

What This Means for the FieldNote Series Ahead

So as I begin to share some of my stories and field notes with you, from Madinah’s blissful and serene atmosphere to Makkah’s intensity, know that they’re not just stories.

They are part of a larger methodological and emotional archive that we naturally build as qualitative researchers, with every place we encounter when we embrace cultural immersion and truly “go to the field.”

The practice of journaling and writing field notes, hence, becomes the foundation of our craft. It strengthens our analysis and our voice. It holds us accountable. And sometimes, it can heal.

Note-taking is not a messy side activity. And it is not just an art. It becomes central to the rigor and integrity of qualitative inquiry. It is how we build trust in our own words, our work, and how we allow others to step into our world with us.

Let these next few entries in The Qualitative Inquisition (Qi) serve as both data and the invitation…

… Facilitating a return to memory, a re-entry into the field, a reflection on what it means to see, feel, and be in the moment—and then write from it.

If this sounds interesting to you, please do join the Qi community!

In Solidarity,

Dr. Elsa

The Qualitative Inquisition (Qi)

References and Resources

(You will also find these in the Resources tab on the main Qi page)

Maharaj, N. (2016). Using field notes to facilitate critical reflection. Reflective Practice, 17, 114 - 124. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2015.1134472.

Pope, C., Ziebland, S., & Mays, N. (2000). Analysing qualitative data. BMJ : British Medical Journal, 320, 114 - 116. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114.

Busetto, L., Wick, W., & Gumbinger, C. (2020). How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurological Research and Practice, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z.

Poth, C., & Searle, M. (2021). Media Review: 30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher (2nd ed.). Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 15, 592 - 594. https://doi.org/10.1177/15586898211028107.

Muswazi, M. T., & Nhamo, E. (2013). Note taking: A lesson for novice qualitative researchers. IOSR Journal of Research & Method in Education, 2(3), 13-17. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285778814_Note_taking_a_lesson_for_novice_qualitative_researchers

ATLAS.ti. (n.d.). What are field notes? Approach & considerations. ATLAS.ti.

https://atlasti.com/guides/qualitative-research-guide-part-2/field-notes

Li, J., He, C., Hu, J., Jia, B., Halevy, A., & Ma, X. (2024). DiaryHelper: Exploring the use of an automatic contextual information recording agent for elicitation diary study. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.19738.

https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.19738

Roller, M. R. (2017, June 26). Rapport & reflection: The pivotal role of note taking in in-depth interview research. Research Design Review.

https://researchdesignreview.com/2017/06/26/rapport-reflection-the-pivotal-role-of-note-taking-in-in-depth-interview-research/

Optimal Workshop. (n.d.). 9 tips to improve your note-taking skills.

https://www.optimalworkshop.com/blog/9-tips-to-improve-your-note-taking-skills/

Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860220137345

Pink, S. (2013). Doing visual ethnography (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Rose, G. (2016). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

Kwik, J. (2020). Limitless: Upgrade your brain, learn anything faster, and unlock your exceptional life. Hay House.

*****

Top News Roundup

U.S.-Brokered Ceasefire in Pakistan and India! - Whew that was close!

Breaches, despite a ceasefire agreement

Explosions in Kashmir - Tensions continue

The First Livestreamed Genocide - Al Jazeera

UNICEF warns Israeli-Gaza Aid Plan will Deepen Suffering for Children

The Sudan Crisis - “Sudan’s war is not just an African Crisis. When will the World Step in?"

Could Trump Recognize Palestine during Gulf visit to Expand Abraham Accords? - The New Arab

*****

TRIVIA

(I have decided to postpone this section for Trivia until after the FieldNote essay series this summer, should there be interest! I will reflect on the format of the newsletter in the meantime for future editions. I appreciate your feedback!)

Previous Trivia Question:

On the flag of Saudi Arabia, there is a sword beneath the Arabic inscription of the Shahada (the Islamic declaration of faith). What does the sword symbolize?

Answer: The sword symbolizes justice, strength, and the defense of Islam.

Check out my piece that talks about the flag and the revolutionary impact of the Pilgrimage in my second newsletter, a special space for creative writing, art, and truthtelling (and do subscribe there too if it resonates!):

*****

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

"The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes." - Marcel Proust